I’m humble for a neurosurgeon, but one thing I think I’m really good at is counseling patients about surgery. I go to great lengths to be sure that the patient understands exactly what is going to happen to them during and after their surgery. I take plenty of time, use plain language and even use images and diagrams to explain the process. With all this effort and thoroughness my patients surely comprehend every facet of their surgery and recovery, right? Wrong. Despite my best efforts, patients have a tough time remembering what was said in pre-surgical discussions. I may think I’ve done a good job at explaining all the potential issues they may face in the first few weeks after surgery but they’re almost certainly not going to remember what I said. Then, when things do get tough, because they will, they’re going to feel scared, alone and maybe even mad at me (I half-jokingly tell every fusion patient they’re going to hate me for the first few weeks after surgery).

Every so often a patient tells me that I should write an article for Spinal (con)Fusion better explaining the patient experience after a surgery like XLIF. They’ll say that despite all my explanation pre-op they just weren’t prepared for the first few weeks after surgery. I kept putting this off until recently a patient, we’ll call her June, offered to keep a journal of her experiences after her XLIF at L4/5. She altruistically kept detailed records to help the next patient who has this procedure. Below are those journal entries. I’ve omitted some extraneous material but for the most part have included all that she’s written (written in italics). When appropriate I’ve added some context at the end of each entry. These entries cover the first month or so of June’s recovery to please bear with the length of this post.

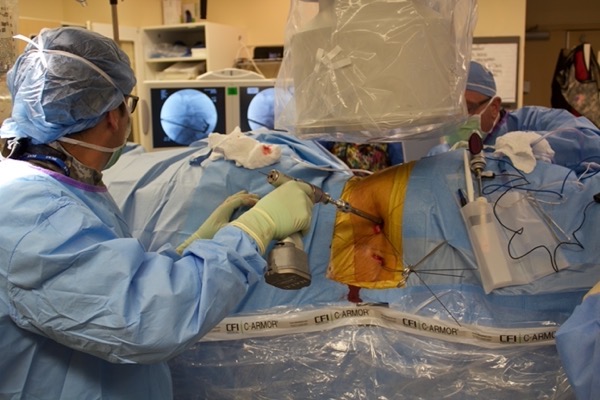

“DAY 1-16: I am a recovering patient of Dr. Thomas’s (female, age 74 in generally good health) and I had my surgery on December 17, 2021. My procedure was XLIF L4-L5, posterior lateral fusion L4-L5 w/percutaneous pedicle screw fixation.”“My first office visit

with Dr. Thomas was thorough and relaxed. I had prepared a list of questions and he was wonderful about answering all of them. He asked me numerous times if he had answered everything, never seeming to be in a hurry to move on to another patient. Our meeting lasted only about 20 minutes, but I came away knowing that I had made the right decision.”

“From the minute I woke up from the surgery, after my prayer of Thanksgiving, I was in a good deal of pain- mostly in the surgical site areas. I was quickly whisked into the recovery room where a wonderful nurse named “Deborah” latched on to me and stayed with me for many hours until I was moved to my room for over-night. She administered pain meds until both she and I were satisfied that I was finally comfortable. This took only a few minutes and the drugs were given via IV. I never really felt groggy or sleepy, but I think it was just my adrenaline.”

“I had a long wait for my hospital room, but I am so fortunate to have a loving husband who was waiting there for me and to spend the night with me. My first time up out of the hospital bed which was aided by a nurse and my husband, AND the hand rails on the bed, was quite challenging. However, I immediately noticed a promise from Dr. Thomas kept! The horrible pain down both my legs that I’d been living with for the past 5 or 6 years was completely gone!!! Yes, there was certainly surgical pain and weakness of my body, but that particular pain was nowhere to be found. I am so elated and dreaming of my days of longer walks and all kinds of things I have not done in such a long time!!”—This is fairly typical of XLIF surgery for radicular pain. Yes there is pain at the incision sites and with hip flexion (from local psoas trauma) but typically, any nerve pain in the legs that was there preop is gone when the patient wakes up.

“We anticipated a short-staff situation at the hospital and we were correct. Any movements that I made had to be assisted (mostly getting out of bed for the bathroom), but I was able to walk with a walker and his support. He never left my side and I think that it’s absolutely necessary for you to have someone with you for an overnight stay after surgery. We had no real issues, but you need that sense of safety and security.”—This is great advice. With the staffing issues at our hospital these days (and at just about every hospital in the country) the nurses are sometimes just spread too thin to ambulate my postop patients as much as I’d like. I can’t stress how important it is to get up out of bed IMMEDIATELY after surgery and start walking; the more the patient can walk that first day, the better. If a family member is present, they can assist with ambulating their loved one.

“This is a time to mention the side rails on the hospital bed. Only when I got home to my normal bed, which isn’t excessively high off the floor, I realized how much I had used those rails in the hospital and did not now have them. I worked out a system with my husband, my bedside table, and then getting to my walker right away. If you are more frail or infirm, you might want to rent some of these bed rails.

They are available. You should not need them for too long, but it depends on you!”—The physical therapists will see XLIF patients before they are discharged to help assess whether or not any equipment like this will be necessary in the first few weeks after surgery.

“I was given pain meds thru the night and kept comfortable for my entire stay. I had to wait the next day for an x-ray of my spine before I could be released and due to the staff shortage, this took several hours just to get me rolled down to x-ray and back to my room. A physical therapist came in before we left and gave us both detailed instructions on how I should get in and out of bed, and how I should climb a few stairs to get into my home. The doctor on-call that day was true to his word and discharged me the minute he could. It was about 6:00 pm and it was a Saturday. DO NOT leave the hospital without a walker and a ‘grabber’. You can’t bend at all, and they are a life-saver!

At home, wear pjs or comfortable, loose clothing, and shoes you can just slide your feet in. You won’t be able to tie laces for a while! You will have good days and bad days, especially the first two weeks. Try not to get discouraged because it is all going to be worth it in the end!!”

“The IV drugs kept me very comfortable. and I remember getting into my car, then my home, then my bed, and thinking- “hmmm, I think I’ve got this!” But do be smart about this. For the first few days I was in a tremendous amount of pain. Everything that I did when I moved, hurt. I hurt all over! I pride myself on being ‘tough’ and started out pushing the pain meds out to the limit, taking much less than was prescribed. So it wasn’t long before I was very uncomfortable. I soon learned to take more meds and stay ahead of the pain.

Also, forcing myself to get up and walk around when I really didn’t want to. I was always glad afterwards, even if very tired. I walked a little more each day and because we had nice weather, I walked outside about day 4 or 5. It was a slow, 15-20 minute walk.”—Sometimes patients will tell me that they don’t want to take the prescribed opioid pain meds because they’re afraid “of getting addicted”. June is so right here. You have to stay ahead of the pain in the first few days because if you get behind it can be very tough to get back on top of it. Take the meds until you’re certain you don’t need them! And you have to make yourself walk!!!

“A side effect of narcotics is constipation, which is not normal for me, so the first few days of my recovery were complicated by this most uncomfortable feeling. I got help from my medical doctor for this issue and it took about two days to resolve. My best advice is to start taking MiraLAX or whatever works for you the very minute you get home. You are already pumped full of narcotics, and the stool softeners they give you at the hospital had no effect on me. Continue Miralax or similar as long as you are taking any narcotics. Medical staff will confirm this!!”—Another great point here. Constipation will make a tough recovery so much tougher!

“You will have good days and bad days, especially the first two weeks of recovery. Having food available is very important, so plan ahead for that. Hopefully, you will have someone that can prepare good food for you at least the first week or so. And, if you are a ‘napper’, have your caregiver rest when you do. They will need it! Try not to get discouraged because it is all going to be worth it in the end!!”—What about your surgeon?? I love naps too!

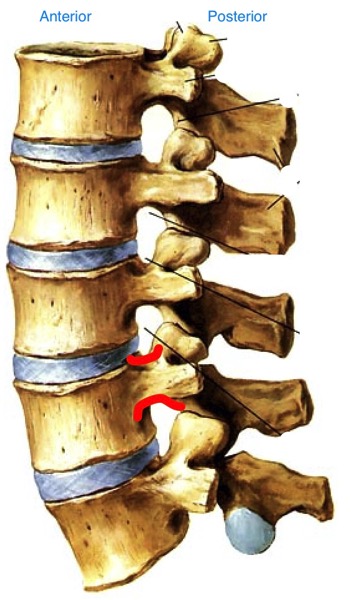

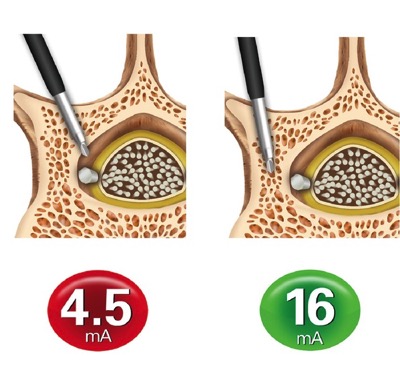

“My first very surprising pain that I do not recall reading about was a muscle spasm in the psoas muscle of my right leg. This is the muscle that Dr. Thomas dilates in order to get to L4-L5. The spasm was one of the worst pains I have ever experienced. It lasted a good 15-20 minutes and was terrifying because at the time, I just didn’t know what was happening. My husband comforted me as I swallowed every type of pain medication available to me which was Tylenol, Dilaudid, Robaxin (muscle relaxer), and Xanax! It finally subsided but left that area of my leg very sore for the next several days. The next morning I phoned Dr. Thomas’s office and Laura Ivey, P.A. was able to speak with me immediately. She eased my worries as soon as she mentioned the ‘psoas muscle’, because I then knew exactly what she was talking about! She urged me to take more pain meds, but that fear of constipation remained looming. Hate it!!! So far, I have had only one, additional, psoas muscle spasm- just as bad as the first one! Unfortunately there is no way to predict if or when these will come.”—This is why I always tell patients that there will be good days and bad days over the first few weeks after surgery. Just when you think you’re in the clear, BAM you encounter a bump in the road. True spasms of the psoas like June had thankfully aren’t that common but psoas pain after XLIF can definitely happen, particularly when the patient tries to flex their hip (like when getting in and out of bed or a car.) This is just surgical pain from psoas dilation, it does not indicate that anything bad is happening and usually is quite short-lived.

“The next ‘surprise’ paincame a few days later when I felt a very strong nerve type pain from my waist through my left buttocks, and all the way down my left leg. It was very similar to the pain I’ve been living with for years, but much, much, more intense. I would say excruciating, unbearable. I tried to wait it out but ended up taking the narcotic. This pain is too much to deal with on your own or with Tylenol. Although I was seeing Dr. Laura Ivey in one more day, I called the office because I knew I could not survive a long time of this kind of pain and suffering. The very helpful triage nurse, Melissa, (who also was available right away), explained that these were the nerves in my body ‘waking up’ and that it was indeed going to be extremely painful. Steroids are most helpful when this happens, and they called some into my drug store immediately. I was so grateful and impressed that I made that call at 9:00 AM, spoke to them, got notified by my drug store, my husband picked up, and I had the meds in my hand by 11:00 AM the same morning. I was astonished at this great attention that I was receiving. We all know this is how it SHOULD be, but not always how it is!! I saw Dr. Laura the next day in the office. It was 13 days after my surgery. I was having a pretty good day and she took her time with me, and we discussed the steroids and how I could modify the dosage (while still taking pain meds and muscle relaxer) since the side effects are very hard on me.”—Transient nerve pains in the legs after any lumbar surgery are not unusual. These pains often resolve spontaneously but sometimes a short course of oral steroids is needed.

“DAY 17 – I am now 17 days from surgery. Each day is pretty much different although I seem to have the very painful ‘nerves waking up’ pain every morning. It starts about 3 or 4 AM, wakes me up, I take the narcotics at that time. But it still takes up to 5 hours for it to go away. I am not taking the full dose of steroids because of the side effects, so this is why it’s taking a little longer to get control of this nerve pain. I am just working thru all of it as best I can. I am following Dr. Thomas’s instructions to the letter about walking and being as active as I can with the NO BLT restrictions. I am unclear how much longer I’ll have this nerve pain. Once the nerve pain resolves, I start to feel more ‘normal’. This makes the afternoons and evenings usually pretty good. I am up to 30-40 minute walks now, once my nerve pain is gone, although I prefer to go slowly and very carefully. Not taking any chances!!! ”

“The first two weeks are by far the worst and having someone with you is absolutely essential. Again, I am so fortunate to have my husband here with me all the time. The first two days I did get up and walk around the house but was in bed otherwise. Getting comfortable in one’s bed is a bit of an ordeal. There is not unbearable pain, but there is a lot of fear of hurting oneself or causing a problem with the pedicle screw fixation. On the third day home, I came into the living room and did not return to bed any more until nighttime. I have no trouble sitting but getting comfortable can be challenging. Some of the mornings when my nerve pain is horrible, I stay in bed longer. But I have been walking 20-30 minutes every day. Mostly outside. I used the walker in the house about 5 days. When we walk outside, I just hang on to my hubby!”

“I have been able to prepare a few very simple meals with help but learning to understand my limits. When I get tired, I quickly sit down and rest. I do experience the results of moving and walking, however. At first, it’s really hard, but you always feel much better afterwards. Even with those excruciating pains, ‘walking’ them out helps. Moving is the key. (p.s. I am not an ‘exerciser’, but I was a walker at least 5 days a week until about 2 years ago when my back pain controlled my life. I retired from an extremely active job just two years ago (owned a flower shop!) The pain made me retire!!! I am totally optimistic and focused on getting back to being more active. Walking and bike riding are my two favorite activities outside.”—One thing I hear a lot from patients is that they’re afraid that they’re going to “knock something loose” like the pedicle screws mentioned in this section of the journal. While I have seen some hardware (mainly the spacer and never the screws) shift in the first month or two after surgery, this is exceptionally rare. Patients should rest comfortably knowing that it would take a tremendous force to dislodge their hardware (I had a patient who was involved in a car accident and nothing happened to the hardware.) June is right here: moving is the key in the first few weeks after surgery!!

“DAY 18– Slightly better night with about 7 hours straight sleep. No drugs taken until 6 AM (last ones were 10:30 PM) which was Tylenol and muscle relaxer, steroid, and one Dilaudid for the nerve pain which still was present but came on a little later this morning. It is also slightly less severe. I continue to take the Miralax once a day as long as I’m using the Dilaudid, a narcotic. It is keeping the constipation at bay but gives you a sort of ‘full’ feeling all day. The steroids which I needed to increase, make me feel jittery and hungry all day too. What can I say? I trust my doctor!! Onward and upward. I know this is temporary for now and going to get BETTER!”—It is imperative that patients take stool softeners while taking pain medications after surgery. A bout of severe constipation will really derail a patient’s recovery!

“DAY 19-Ok! So, coming off a great day like yesterday, the sad truth is that I was hit this morning at 3:30 AM by the strongest, most intense, ‘nerves waking up’ pain since my surgery!!! I’ve never actually been ‘on fire’. But that is what I imagine when I feel this pain. It starts on the left side of my surgical site in my low back and travels all the way down my leg. It is constant and grows in intensity. At first inkling of this, I got up as quickly as possible and took one Dilaudid, 2 Tylenol, one steroid tablet, and 1 Robaxin (muscle relaxer).

I waited two hours with no relief. I got up and tried walking all around the house, still no relief. At 9 AM I still had no real relief. So, I repeated all the same medicines but this time I took three Tylenol in the mix and continued to walk around the house to see if that would help. About two hours later, I began to feel about a 20 per cent reduction of the intensity of the pain. It’s 3 PM now and I continue to feel sore and exhausted. Never have been back to sleep. I’ve done very little except the ‘house’ walking and got a shower. No need to call Dr. Laura, I know what this is, but today has been the worst. ☹ It’s amazing how excruciating pain can affect a person. Can’t wait for tomorrow because it HAS to be better!”—More waxing and waning of symptoms here. Again, this is totally normal in the first few weeks after surgery. Thankfully June has seen this before and isn’t too concerned about it. I truly believe it’s this positive outlook that has been key to her good recovery so far.

“DAY 22-To update from Day 19, the past two days have been much improved. I have had many hours of zero nerve pain; however, I did experience a long-lasting period of nerve pain in the same area of my left leg last night starting around 8 pm. It started to grow in intensity so I took a Dilaudid at 9 pm, along with Tylenol and Robaxin. At 10 I took my .01mg Xanax. It took me several hours, but I was able to finally fall asleep around midnight without taking additional meds until 2 AM. I woke again for the bathroom and took more Tylenol, Robaxin, and one steroid at that time. This morning I have slight discomfort in the left leg radiating from the hip joint, on left side of my body. I’m up and moving around and plan to have a good day! My wish is to have a discussion with Dr. Laura Ivey or Dr. Thomas about this nerve pain. Is my problem a normal one? Will this be on-going and for how long? Is there anything that I can do to make it stop? Am I doing something to bring it on?“—Here we see the nerve pain starting to improve a bit. Every patient’s recovery from XLIF is different and I can’t say that June’s “nerve pain” is typical. We’ve seen just about every unusual new neurological symptom after XLIF, though, and I’m no longer surprised when a patient hits a bump in the road like this. Thankfully these new symptoms are almost always very self-limited (and almost always respond to some oral steroids) and don’t affect long-term outcome.

“DAY 28- I thought this would be a good day to write an update on my recovery as I am just three days away from a full month after my spine fusion surgery. I awoke with a feeling of tremendous gratefulness to God, Dr. Thomas, his entire staff, my husband and all my supportive friends and family! I had a big bunch of flowers to arrange after breakfast which always makes me SO happy! I know that the worst is

all behind me and I am so happy that I was able to get my surgery in mid-December and it’s OVER! If not, I might still be waiting for the January 29th date that was given to me originally.”

“I have one more full month of very restrictive movements as far as bending, twisting and lifting goes. I’ve been very good about following those orders and my husband watches me like a hawk if I accidentally start to make a little ‘slip’. But I have been walking

outside with my husband every day for a minimum of 30 minutes. It has been cold, but mostly sunny and the walks are sometimes challenging but always give me a feeling of accomplishment. I find that when the cold air hits my body, I get a dull ache at the surgical site on my back, but it is far from debilitating. I’m sure this is a temporary effect and if it lingers after the walk, two Tylenol tablets is all I need to get rid of the very slight pain. I don’t even need Tylenol every day. At this point, I am not taking any prescribed pain medications, muscle relaxers, MiraLAX or laxatives. Everything is working ‘normally’, and I really feel good!”

“I am cooking several meals a week now which makes my husband very happy. I have always loved to cook, and this is another way I feel a sense of accomplishment. One unexpected result of my surgery and recovery experience is that my husband and I have grown closer- even after 37 years of marriage!!!! We have been together pretty much 24/7 since all this started and while I tell him daily how much I appreciate him; he is also full of praise for my daily progress and reminds me how proud he is of me and how much he loves me.”—Honestly June and her husband are the sweetest.

“I will be getting an x-ray in about 10 more days and will see Dr. Laura Ivey as a follow up to that. I am anxious for that report, but expect only good news! I have a friend in my own neighborhood who has already been through a similar surgery already twice (not from Dr. Thomas) and he has not had a good result. I have urged him to get a second opinion from Dr. Thomas as his next step.”

“Day 80– Yes! Day 80!!! After recently reviewing my previous blog entries, I think it is important to share the great progress that I’ve made since my last entry. Re-reading the first few weeks of struggle and pain, seems much longer ago than it actually is. While I understand that my procedure does require six months for a full recovery, I can say that my husband and I feel that at the almost 3 month mark, I am very close to mostly normal activities. On rare occasions, I require a muscle relaxer after working in my garden because of back pain, but otherwise, I am not taking any prescription or OTC drugs. My greatest ‘problem’ is worrying that I’ll make a move or take a fall that might damage Dr. Thomas’s excellent surgical procedure that corrected my spondylolisthesis. A week ago, I was able to have a 3-day weekend in Charleston with my adult granddaughter. We took long walking tours as well as stopped in as many shops as time allowed. A short 4 months ago, this would have been an impossible activity for me because of the extreme leg and back pain that I had on a daily basis.”

“It goes without saying that I really feel that I have my life back, which is exactly what I asked Dr. Thomas for on our first meeting. Another patient of Dr. Thomas’ told me that after surgery, he felt he had taken a ‘magic pill’. While I remain careful, and cautiously optimistic, I am making the most of every ‘magic’, and pain free moment of every day! I am considering returning to some type of work on a part-time basis as well. I want to be as productive as possible!!”

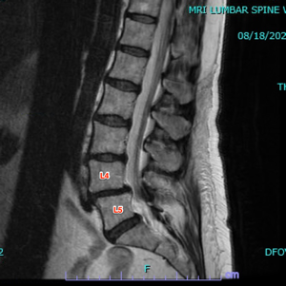

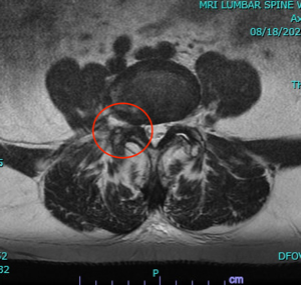

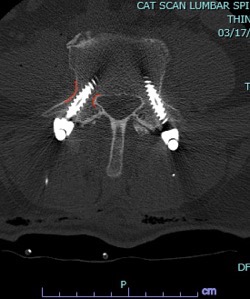

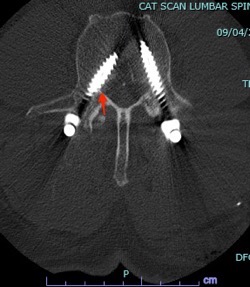

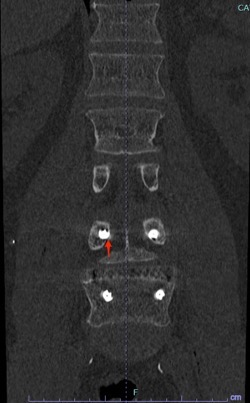

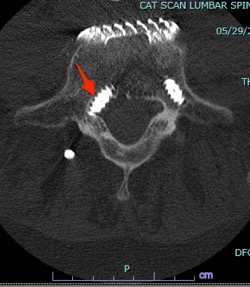

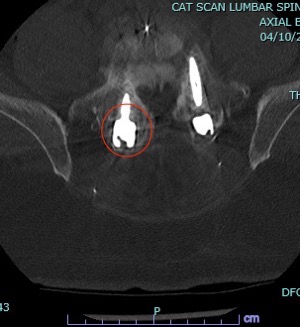

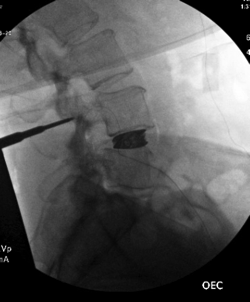

There you have it, a very detailed account of what it’s like in the first couple of months after XLIF. June clearly hit some bumps along the way in her recovery. New (often debilitating) neurological symptoms are not uncommon in the first few weeks after XLIF. That can happen when reconstructing one’s spine and undoing years of degenerative damage. As June demonstrated, though, the key is to not get discouraged by the short-term setbacks and to focus on the long-term result. In the end, because of her amazingly positive outlook, June had an excellent recovery after her XLIF. I’m so proud of her and am thrilled to share her story. (See figures 1 and 2)

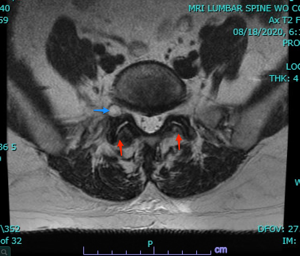

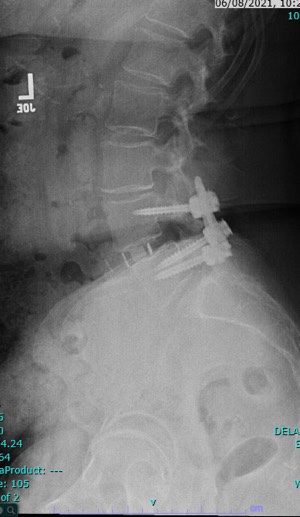

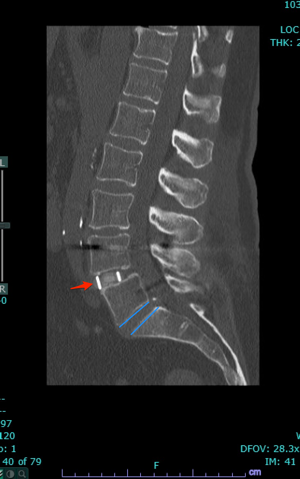

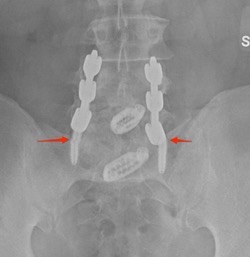

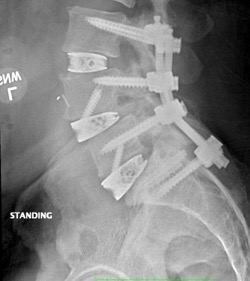

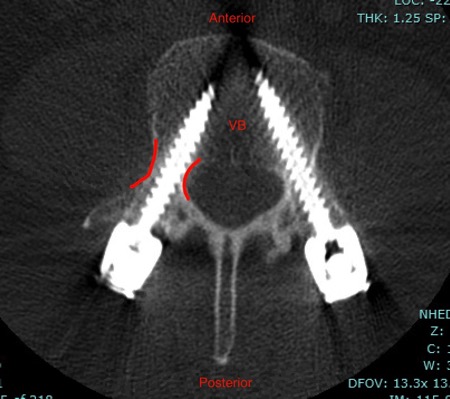

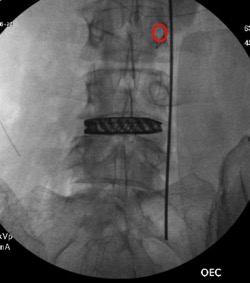

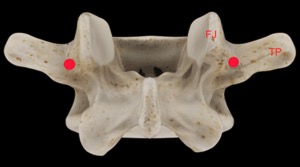

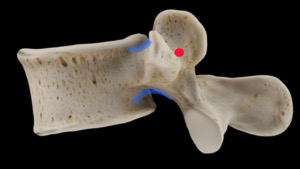

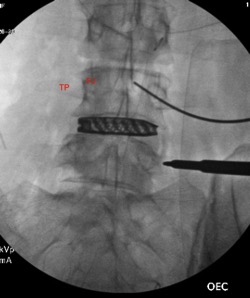

Figure 1: Pre- and postoperative Xrays showing a complete reduction of June’s spondylolisthesis at L4/5. Note the spacer and pedicle screws implanted during XLIF.

Figure 2: One happy patient! She made it look easy!

Thanks for reading!

J. Alex Thomas, M.D.